A New Way to Share the Songs You’ve Written on Spotify

We’re expanding our suite of songwriting promotional tools, which helps fans, collaborators, and industry partners discover more about the creators behind their favorite songs.

Get the most out of Spotify with resources to supercharge your songwriting career — whether you're performing your own lyrics or writing for others.

Discover Spotify-powered opportunities to create music, connect with other visionaries, and promote your work.

Get global analytics that help you understand your catalog and land the best opportunities for your roster of songwriters and producers.

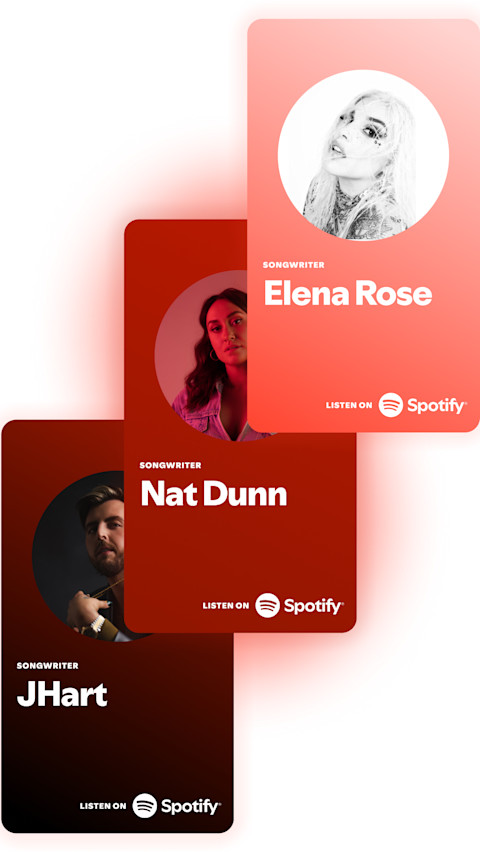

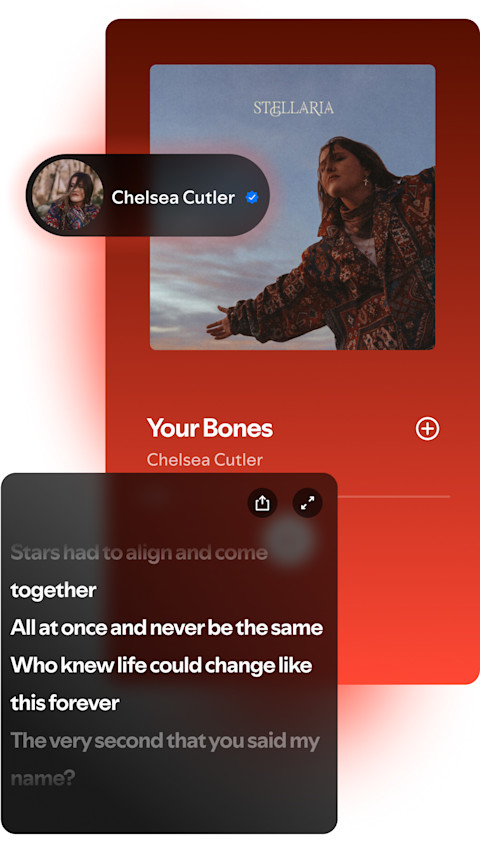

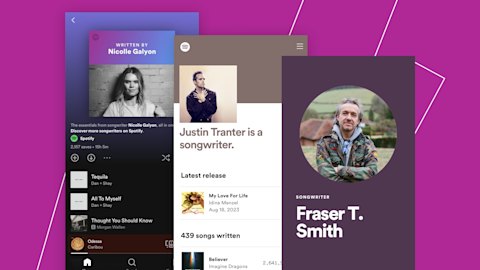

Songwriter Pages can showcase your written work, attract potential collaborators, and expand your industry network. They're digital songwriting resumes that spark career-building opportunities anywhere, any time.

Written By playlists are fan-facing versions of Songwriter Pages. They increase exposure to new audiences, deepen relationships with current fans, and maximize discoverability on Spotify by allowing listeners to hear your career-spanning works.

Clickable, in-app song credits on Spotify enable fans, fellow creators, publishers, and music supervisors to dive deeper into the music they love and discover those who wrote and produced it.

We’re expanding our suite of songwriting promotional tools, which helps fans, collaborators, and industry partners discover more about the creators behind their favorite songs.

Martin Maguire, Head of Publisher Support and Relationships at PRS for Music shares advice for songwriters starting their careers.

Singer and songwriter Justin Tranter has worked on hits with artists like Selena Gomez, Justin Bieber, and Halsey. In this episode Justin talks about believing in yourself, working hard, and the intricacies of the business side of the industry.

What's the best way to get your music in the ears of music supervisors? What is an operating agreement? Why is knowing when to press pause so important? All these questions and more—answered.

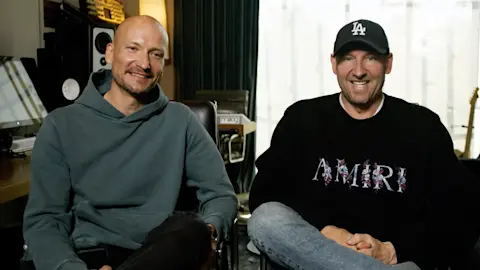

Songwriting and production powerhouse duo Stargate (Mikkel S. Eriksen and Tor E. Hermansen) has worked on hits with artists like Rihanna, Coldplay, Katy Perry, and Beyoncé.